Chapter 10. Imaginary Journeys: The Lojban Space/Time Tense System

10.1. Introductory

This chapter attempts to document and explain the space/time tense system of Lojban. It does not attempt to answer all questions of the form “How do I say such-and-such (an English tense) in Lojban?” Instead, it explores the Lojban tense system from the inside, attempting to educate the reader into a Lojbanic viewpoint. Once the overall system is understood and the resources that it makes available are familiar, the reader should have some hope of using appropriate tense constructs and being correctly understood.

The system of Lojban tenses presented here may seem really complex because of all the pieces and all the options; indeed, this chapter is the longest one in this book. But tense is in fact complex in every language. In your native language, the subtleties of tense are intuitive. In foreign languages, you are seldom taught the entire system until you have reached an advanced level. Lojban tenses are extremely systematic and productive, allowing you to express subtleties based on what they mean rather than on how they act similarly to English tenses. This chapter concentrates on presenting an intuitive approach to the meaning of Lojban tense words and how they may be creatively and productively combined.

What is “tense”? Historically, “tense” is the attribute of verbs in English and related languages that expresses the time of the action. In English, three tenses are traditionally recognized, conventionally called the past, the present, and the future. There are also a variety of compound tenses used in English. However, there is no simple relationship between the form of an English tense and the time actually expressed:

- I go to London tomorrow.

- I will go to London tomorrow.

- I am going to London tomorrow.

all mean the same thing, even though the first sentence uses the present tense; the second, the future tense; and the third, a compound tense usually called “present progressive”. Likewise, a newspaper headline says “JONES DIES”, although it is obvious that the time referred to must be in the past. Tense is a mandatory category of English: every sentence must be marked for tense, even if in a way contrary to logic, because every main verb has a tense marker built into to it. By contrast, Lojban brivla have no implicit tense marker attached to them.

In Lojban, the concept of tense extends to every selbri, not merely the verb-like ones. In addition, tense structures provide information about location in space as well as in time. All tense information is optional in Lojban: a sentence like:

Example 10.1.

mi

I

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi klama le zarci

I go-to the market.

can be understood as:

- I went to the market.

- I am going to the market.

- I have gone to the market.

- I will go to the market.

- I continually go to the market.

as well as many other possibilities: context resolves which is correct.

The placement of a tense construct within a Lojban bridi is easy: right before the selbri. It goes immediately after the cu, and can in fact always replace the cu (although in very complex sentences the rules for eliding terminators may be changed as a result). In the following examples, pu is the tense marker for “past time”:

Example 10.2.

mi

mi

I

cu

pu

pu

in-the-past

klama

klama

go-to

le

le

the

zarci

zarci

market.

mi cu pu klama le zarci

mi pu klama le zarci

I in-the-past go-to the market.

I went to the market.

It is also possible to put the tense somewhere else in the bridi by adding ku after it. This ku is an elidable terminator, but it's almost never possible to actually elide it except at the end of the bridi:

Example 10.3.

puku

In-the-past

mi

I

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

puku mi klama le zarci

In-the-past I go-to the market.

Earlier, I went to the market.

Example 10.4.

mi

I

klama

go-to

puku

in-the-past

le

the

zarci

market.

mi klama puku le zarci

I go-to in-the-past the market.

I went earlier to the market.

Example 10.5.

mi

I

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market

pu

in-the-past.

[ku]

mi klama le zarci pu [ku]

I go-to the market in-the-past.

I went to the market earlier.

Example 10.2 through Example 10.5 are different only in emphasis. Abnormal order, such as Example 10.3 through Example 10.5 exhibit, adds emphasis to the words that have been moved; in this case, the tense cmavo pu. Words at either end of the sentence tend to be more noticeable.

10.2. Spatial tenses: FAhA and VA

The following cmavo are discussed in this section:

| vi | VA | short distance |

| va | VA | medium distance |

| vu | VA | long distance |

| zu'a | FAhA | left |

| ri'u | FAhA | right |

| ga'u | FAhA | up |

| ni'a | FAhA | down |

| ca'u | FAhA | front |

| ne'i | FAhA | within |

| be'a | FAhA | north of |

(The complete list of FAhA cmavo can be found in Section 10.27.)

Why is this section about spatial tenses rather than the more familiar time tenses of Section 10.1, asks the reader? Because the model to be used in explaining both will be easier to grasp for space than for time. The explanation of time tenses will resume in Section 10.4.

English doesn't have mandatory spatial tenses. Although there are plenty of ways in English of showing where an event happens, there is absolutely no need to do so. Considering this fact may give the reader a feel for what the optional Lojban time tenses are like. From the Lojban point of view, space and time are interchangeable, although they are not treated identically.

Lojban specifies the spatial tense of a bridi (the place at which it occurs) by using words from selma'o FAhA and VA to describe an imaginary journey from the speaker to the place referred to. FAhA cmavo specify the direction taken in the journey, whereas VA cmavo specify the distance gone. For example:

Example 10.6.

le

The

nanmu

man

va

[medium-distance]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu va batci le gerku

The man [medium-distance] bites the dog.

Over there the man is biting the dog.

What is at a medium distance? The event referred to by the bridi: the man biting the dog. What is this event at a medium distance from? The speaker's location. We can understand the va as saying: “If you want to get from the speaker's location to the location of the bridi, journey for a medium distance (in some direction unspecified).” This “imaginary journey” can be used to understand not only Example 10.6, but also every other spatial tense construct.

Suppose you specify a direction with a FAhA cmavo, rather than a distance with a VA cmavo:

Example 10.7.

le

The

nanmu

man

zu'a

[left]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu zu'a batci le gerku

The man [left] bites the dog.

Here the imaginary journey is again from the speaker's location to the location of the bridi, but it is now performed by going to the left (in the speaker's reference frame) for an unspecified distance. So a reasonable translation is:

To my left, the man bites the dog.

The “my” does not have an explicit equivalent in the Lojban, because the speaker's location is understood as the starting point.

(Etymologically, by the way, zu'a is derived from zunle, the gismu for “left”, whereas vi, va, and vu are intended to be reminiscent of ti, ta, and tu, the demonstrative pronouns “this-here”, “that-there”, and “that-yonder”.)

What about specifying both a direction and a distance? The rule here is that the direction must come before the distance:

Example 10.8.

le

The

nanmu

man

zu'avi

[left-short-distance]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu zu'avi batci le gerku

The man [left-short-distance] bites the dog.

Slightly to my left, the man bites the dog.

As explained in Section 10.1, it would be perfectly correct to use ku to move this tense to the beginning or the end of the sentence to emphasize it:

Example 10.9.

zu'aviku

[Left-short-distance]

le

the

nanmu

man

cu

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

zu'aviku le nanmu cu batci le gerku

[Left-short-distance] the man bites the dog.

Slightly to my left, the man bites the dog.

10.3. Compound spatial tenses

Humph, says the reader: this talk of “imaginary journeys” is all very well, but what's the point of it? – zu'a means “on the left” and vi means “nearby”, and there's no more to be said. The imaginary-journey model becomes more useful when so-called compound tenses are involved. A compound tense is exactly like a simple tense, but has several FAhAs run together:

Example 10.10.

le

The

nanmu

man

ga'u

[up]

zu'a

[left]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu ga'u zu'a batci le gerku

The man [up] [left] bites the dog.

The proper interpretation of Example 10.10 is that the imaginary journey has two stages: first move from the speaker's location upward, and then to the left. A translation might read:

Left of a place above me, the man bites the dog.

(Perhaps the speaker is at the bottom of a manhole, and the dog-biting is going on at the edge of the street.)

In the English translation, the keywords “left” and “above” occur in reverse order to the Lojban order. This effect is typical of what happens when we “unfold” Lojban compound tenses into their English equivalents, and shows why it is not very useful to try to memorize a list of Lojban tense constructs and their colloquial English equivalents.

The opposite order also makes sense:

Example 10.11.

le

The

nanmu

man

zu'a

[left]

ga'u

[up]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu zu'a ga'u batci le gerku

The man [left] [up] bites the dog.

Above a place to the left of me, the man bites the dog.

In ordinary space, the result of going up and then to the left is the same as that of going left and then up, but such a simple relationship does not apply in all environments or to all directions: going south, then east, then north may return one to the starting point, if that point is the North Pole.

Each direction can have a distance following:

Example 10.12.

le

The

nanmu

man

zu'avi

[left-short-distance]

ga'u

[up]

vu

[long-distance]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu zu'avi ga'u vu batci le gerku

The man [left-short-distance] [up] [long-distance] bites the dog.

Far above a place slightly to the left of me, the man bites the dog.

A distance can also come at the beginning of the tense construct, without any specified direction. (Example 10.6, with VA alone, is really a special case of this rule when no directions at all follow.)

Example 10.13.

le

The

nanmu

man

vi

[short-distance]

zu'a

[left]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu vi zu'a batci le gerku

The man [short-distance] [left] bites the dog.

Left of a place near me, the man bites the dog.

Any number of directions may be used in a compound tense, with or without specified distances for each:

Example 10.14.

le

The

ne'i

[within]

nanmu

man

batci

bites

ca'u

[front]

le

the

vi

[short]

gerku

dog.

ni'a

[down]

va

[medium]

ri'u

[right]

vu

[long]

le nanmu ca'u vi ni'a va ri'u vu

The man [front] [short] [down] [medium] [right] [long]

ne'i batci le gerku

[within] bites the dog.

Within a place a long distance to the right of a place which is a medium distance downward from a place a short distance in front of me, the man bites the dog.

Whew! It's a good thing tense constructs are optional: having to say all that could certainly be painful. Note, however, how much shorter the Lojban version of Example 10.14 is than the English version.

10.4. Temporal tenses: PU and ZI

The following cmavo are discussed in this section:

| pu | PU | past |

| ca | PU | present |

| ba | PU | future |

| zi | ZI | short time distance |

| za | ZI | medium time distance |

| zu | ZI | long time distance |

Now that the reader understands spatial tenses, there are only two main facts to understand about temporal tenses: they work exactly like the spatial tenses, with selma'o PU and ZI standing in for FAhA and VA; and when both spatial and temporal tense cmavo are given in a single tense construct, the temporal tense is expressed first. (If space could be expressed before or after time at will, then certain constructions would be ambiguous.)

Example 10.15.

le

The

nanmu

man

pu

[past]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu pu batci le gerku

The man [past] bites the dog.

The man bit the dog.

means that to reach the dog-biting, you must take an imaginary journey through time, moving towards the past an unspecified distance. (Of course, this journey is even more imaginary than the ones talked about in the previous sections, since time-travel is not an available option.)

Lojban recognizes three temporal directions: pu for the past, ca for the present, and ba for the future. (Etymologically, these derive from the corresponding gismu purci, cabna, and balvi. See Section 10.23 for an explanation of the exact relationship between the cmavo and the gismu.) There are many more spatial directions, since there are FAhA cmavo for both absolute and relative directions as well as “direction-like relationships” like “surrounding”, “within”, “touching”, etc. (See Section 10.27 for a complete list.) But there are really only two directions in time: forward and backward, toward the future and toward the past. Why, then, are there three cmavo of selma'o PU?

The reason is that tense is subjective: human beings perceive space and time in a way that does not necessarily agree with objective measurements. We have a sense of “now” which includes part of the objective past and part of the objective future, and so we naturally segment the time line into three parts. The Lojban design recognizes this human reality by providing a separate time-direction cmavo for the “zero direction”, Similarly, there is a FAhA cmavo for the zero space direction: bu'u, which means something like “coinciding”.

(Technical note for readers conversant with relativity theory: The Lojban time tenses reflect time as seen by the speaker, who is assumed to be a “point-like observer” in the relativistic sense: they do not say anything about physical relationships of relativistic interval, still less about implicit causality. The nature of tense is not only subjective but also observer-based.)

Here are some examples of temporal tenses:

Example 10.16.

le

The

nanmu

man

puzi

[past-short-distance]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu puzi batci le gerku

The man [past-short-distance] bites the dog.

A short time ago, the man bit the dog.

Example 10.17.

le

The

nanmu

man

pu

[past]

pu

[past]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu pu pu batci le gerku

The man [past] [past] bites the dog.

Earlier than an earlier time than now, the man bit the dog.

The man had bitten the dog.

The man had been biting the dog.

Example 10.18.

le

The

nanmu

man

ba

[future]

puzi

[past-short]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu ba puzi batci le gerku

The man [future] [past-short] bites the dog.

Shortly earlier than some time later than now, the man will bite the dog.

Soon before then, the man will have bitten the dog.

The man will have just bitten the dog.

The man will just have been biting the dog.

What about the analogue of an initial VA without a direction? Lojban does allow an initial ZI with or without following PUs:

Example 10.19.

le

The

nanmu

man

zi

[short]

pu

[past]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu zi pu batci le gerku

The man [short] [past] bites the dog.

Before a short time from or before now, the man bit or will bite the dog.

Example 10.20.

le

The

nanmu

man

zu

[long]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu zu batci le gerku

The man [long] bites the dog.

A long time from or before now, the man will bite or bit the dog.

Example 10.19 and Example 10.20 are perfectly legitimate, but may not be very much used: zi by itself signals an event that happens at a time close to the present, but without saying whether it is in the past or the future. A rough translation might be “about now, but not exactly now”.

Because we can move in any direction in space, we are comfortable with the idea of events happening in an unspecified space direction (“nearby” or “far away”), but we live only from past to future, and the idea of an event which happens “nearby in time” is a peculiar one. Lojban provides lots of such possibilities that don't seem all that useful to English-speakers, even though you can put them together productively; this fact may be a limitation of English.

Finally, here are examples which combine temporal and spatial tense:

Example 10.21.

le

The

nanmu

man

puzu

[past-long-time]

vu

[long-space]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

le nanmu puzu vu batci le gerku

The man [past-long-time] [long-space] bites the dog.

Long ago and far away, the man bit the dog.

Alternatively,

Example 10.22.

le

The

nanmu

man

cu

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog

puzuvuku

[past-long-time-long-space].

le nanmu cu batci le gerku puzuvuku

The man bites the dog [past-long-time-long-space].

The man bit the dog long ago and far away.

10.5. Interval sizes: VEhA and ZEhA

The following cmavo are discussed in this section:

| ve'i | VEhA | short space interval |

| ve'a | VEhA | medium space interval |

| ve'u | VEhA | long space interval |

| ze'i | ZEhA | short time interval |

| ze'a | ZEhA | medium time interval |

| ze'u | ZEhA | long time interval |

So far, we have considered only events that are usually thought of as happening at a particular point in space and time: a man biting a dog at a specified place and time. But Lojbanic events may be much more “spread out” than that: mi vasxu (I breathe) is something which is true during the whole of my life from birth to death, and over the entire part of the earth where I spend my life. The cmavo of VEhA (for space) and ZEhA (for time) can be added to any of the tense constructs we have already studied to specify the size of the space or length of the time over which the bridi is claimed to be true.

Example 10.23.

le

The

verba

child

ve'i

[small-space-interval]

cadzu

walks-on

le

the

bisli

ice.

le verba ve'i cadzu le bisli

The child [small-space-interval] walks-on the ice.

In a small space, the child walks on the ice.

The child walks about a small area of the ice.

means that her walking was done in a small area. Like the distances, the interval sizes are classified only roughly as “small, medium, large”, and are relative to the context: a small part of a room might be a large part of a table in that room.

Here is an example using a time interval:

Example 10.24.

le

The

verba

child

ze'a

[medium-time-interval]

cadzu

walks-on

le

the

bisli

ice.

le verba ze'a cadzu le bisli

The child [medium-time-interval] walks-on the ice.

For a medium time, the child walks/walked/will walk on the ice.

Note that with no time direction word, Example 10.24 does not say when the walking happened: that would be determined by context. It is possible to specify both directions or distances and an interval, in which case the interval always comes afterward:

Example 10.25.

le

The

verba

child

pu

[past]

ze'a

[medium-time-interval]

cadzu

walks-on

le

the

bisli

ice.

le verba pu ze'a cadzu le bisli

The child [past] [medium-time-interval] walks-on the ice.

For a medium time, the child walked on the ice.

The child walked on the ice for a while.

In Example 10.25, the relationship of the interval to the specified point in time or space is indeterminate. Does the interval start at the point, end at the point, or is it centered on the point? By adding an additional direction cmavo after the interval, this question can be conclusively answered:

Example 10.26.

mi

I

ca

[present]

ze'ica

[short-time-interval-present]

cusku

express

dei

this-utterance.

mi ca ze'ica cusku dei

I [present] [short-time-interval-present] express this-utterance.

I am now saying this sentence.

means that for an interval starting a short time in the past and extending to a short time in the future, I am expressing the utterance which is Example 10.26. Of course, “short” is relative, as always in tenses. Even a long sentence takes up only a short part of a whole day; in a geological context, the era of Homo sapiens would only be a ze'i interval.

By contrast,

Example 10.27.

mi

I

ca

[present]

ze'ipu

[short-time-interval-past]

cusku

express

dei

this-utterance.

mi ca ze'ipu cusku dei

I [present] [short-time-interval-past] express this-utterance.

I have just been saying this sentence.

means that for a short time interval extending from the past to the present I have been expressing Example 10.27. Here the imaginary journey starts at the present, lays down one end point of the interval, moves into the past, and lays down the other endpoint. Another example:

Example 10.28.

mi

I

pu

[past]

ze'aba

[medium-time-interval-future]

citka

eat

le

the

mi

of-me

sanmi

meal.

mi pu ze'aba citka le mi sanmi

I [past] [medium-time-interval-future] eat the of-me meal.

For a medium time afterward, I ate my meal.

I ate my meal for a while.

With ca instead of ba, Example 10.28 becomes Example 10.29,

Example 10.29.

mi

I

pu

[past]

ze'aca

[medium-time-interval-present]

citka

eat

le

the

mi

of-me

sanmi

meal.

mi pu ze'aca citka le mi sanmi

I [past] [medium-time-interval-present] eat the of-me meal.

For a medium time before and afterward, I ate my meal.

I ate my meal for a while.

because the interval would then be centered on the past moment rather than oriented toward the future of that moment. The colloquial English translations are the same – English is not well-suited to representing this distinction.

Here are some examples of the use of space intervals with and without specified directions:

Example 10.30.

ta

That-there

ri'u

[right]

ve'i

[short-space-interval]

finpe

is-a-fish.

ta ri'u ve'i finpe

That-there [right] [short-space-interval] is-a-fish.

That thing on my right is a fish.

In Example 10.30, there is no equivalent in the colloquial English translation of the “small interval” which the fish occupies. Neither the Lojban nor the English expresses the orientation of the fish. Compare Example 10.31:

Example 10.31.

ta

That-there

ri'u

[right]

ve'ica'u

[short-space-interval-front]

finpe

is-a-fish.

ta ri'u ve'ica'u finpe

That-there [right] [short-space-interval-front] is-a-fish.

That thing on my right extending forwards is a fish.

Here the space interval occupied by the fish extends from a point on my right to another point in front of the first point.

10.6. Vague intervals and non-specific tenses

What is the significance of failing to specify an interval size of the type discussed in Section 10.5? The Lojban rule is that if no interval size is given, the size of the space or time interval is left vague by the speaker. For example:

Example 10.32.

mi

I

pu

[past]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi pu klama le zarci

I [past] go-to the market.

really means:

At a moment in the past, and possibly other moments as well, the event “I went to the market” was in progress.

The vague or unspecified interval contains an instant in the speaker's past. However, there is no indication whether or not the whole interval is in the speaker's past! It is entirely possible that the interval during which the going-to-the-market is happening stretches into the speaker's present or even future.

Example 10.32 points up a fundamental difference between Lojban tenses and English tenses. An English past-tense sentence like “I went to the market” generally signifies that the going-to-the-market is entirely in the past; that is, that the event is complete at the time of speaking. Lojban pu has no such implication.

This property of a past tense is sometimes called “aorist”, in reference to a similar concept in the tense system of Classical Greek. All of the Lojban tenses have the same property, however:

Example 10.33.

le

The

tricu

tree

ba

[future]

crino

is-green.

le tricu ba crino

The tree [future] is-green.

The tree will be green.

does not imply (as the colloquial English translation does) that the tree is not green now. The vague interval throughout which the tree is, in fact, green may have already started.

This general principle does not mean that Lojban has no way of indicating that a tree will be green but is not yet green. Indeed, there are several ways of expressing that concept: see Section 10.10 (event contours) and Section 10.20 (logical connection between tenses).

10.7. Dimensionality: VIhA

The following cmavo are discussed in this section:

| vi'i | VIhA | on a line |

| vi'a | VIhA | in an area |

| vi'u | VIhA | through a volume |

| vi'e | VIhA | throughout a space/time interval |

The cmavo of ZEhA are sufficient to express time intervals. One fundamental difference between space and time, however, is that space is multi-dimensional. Sometimes we want to say not only that something moves over a small interval, but also perhaps that it moves in a line. Lojban allows for this. I can specify that a motion “in a small space” is more specifically “in a short line”, “in a small area”, or “through a small volume”.

What about the child walking on the ice in Example 10.23 through Example 10.25? Given the nature of ice, probably the area interpretation is most sensible. I can make this assumption explicit with the appropriate member of selma'o VIhA:

Example 10.34.

le

The

verba

child

ve'a

[medium-space-interval]

vi'a

[2-dimensional]

cadzu

walks-on

le

the

bisli

ice.

le verba ve'a vi'a cadzu le bisli

The child [medium-space-interval] [2-dimensional] walks-on the ice.

In a medium-sized area, the child walks on the ice.

Space intervals can contain either VEhA or VIhA or both, but if both, VEhA must come first, as Example 10.34 shows.

The reader may wish to raise a philosophical point here. (Readers who don't wish to, should skip this paragraph.) The ice may be two-dimensional, or more accurately its surface may be, but since the child is three-dimensional, her walking must also be. The subjective nature of Lojban tense comes to the rescue here: the action is essentially planar, and the third dimension of height is simply irrelevant to walking. Even walking on a mountain could be called vi'a, because relatively speaking the mountain is associated with an essentially two-dimensional surface. Motion which is not confined to such a surface (e.g., flying, or walking through a three-dimensional network of tunnels, or climbing among mountains rather than on a single mountain) would be properly described with vi'u. So the cognitive, rather than the physical, dimensionality controls the choice of VIhA cmavo.

VIhA has a member vi'e which indicates a 4-dimensional interval, one that involves both space and time. This allows the spatial tenses to invade, to some degree, the temporal tenses; it is possible to make statements about space-time considered as an Einsteinian whole. (There are presently no cmavo of FAhA assigned to “pastward” and “futureward” considered as space rather than time directions – they could be added, though, if Lojbanists find space-time expression useful.) If a temporal tense cmavo is used in the same tense construct with a vi'e interval, the resulting tense may be self-contradictory.

10.8. Movement in space: MOhI

The following cmavo is discussed in this section:

| mo'i | MOhI | movement flag |

All the information carried by the tense constructs so far presented has been presumed to be static: the bridi is occurring somewhere or other in space and time, more or less remote from the speaker. Suppose the truth of the bridi itself depends on the result of a movement, or represents an action being done while the speaker is moving? This too can be represented by the tense system, using the cmavo mo'i (of selma'o MOhI) plus a spatial direction and optional distance; the direction now refers to a direction of motion rather than a static direction from the speaker.

Example 10.35.

le

The

verba

child

mo'i

[movement]

ri'u

[right]

cadzu

walks-on

le

the

bisli

ice.

le verba mo'i ri'u cadzu le bisli

The child [movement] [right] walks-on the ice.

The child walks toward my right on the ice.

This is quite different from:

Example 10.36.

le

The

verba

child

ri'u

[right]

cadzu

walks-on

le

the

bisli

ice.

le verba ri'u cadzu le bisli

The child [right] walks-on the ice.

To the right of me, the child walks on the ice.

In either case, however, the reference frame for defining “right” and “left” is the speaker's, not the child's. This can be changed thus:

Example 10.37.

le

The

verba

child

mo'i

[movement]

ri'u

[right]

cadzu

walks-on

le

the

bisli

ice

ma'i

in-reference-frame

vo'a

the-x1-place.

le verba mo'i ri'u cadzu le bisli ma'i vo'a

The child [movement] [right] walks-on the ice in-reference-frame the-x1-place.

The child walks toward her right on the ice.

Example 10.37 is analogous to Example 10.35. The cmavo ma'i belongs to selma'o BAI (explained in Section 9.6), and allows specifying a reference frame.

Both a regular and a mo'i-flagged spatial tense can be combined, with the mo'i construct coming last:

Example 10.38.

le

The

verba

child

zu'avu

[left-long]

mo'i

[movement]

ri'uvi

[right-short]

cadzu

walks-on

le

the

bisli

ice.

le verba zu'avu mo'i ri'uvi cadzu le bisli

The child [left-long] [movement] [right-short] walks-on the ice.

Far to the left of me, the child walks a short distance toward my right on the ice.

It is not grammatical to use multiple directions like zu'a ca'u after mo'i, but complex movements can be expressed in a separate bridi.

Here is an example of a movement tense on a bridi not inherently involving movement:

Example 10.39.

mi

I

mo'i

[movement]

ca'uvu

[front-long]

citka

eat

le

the

mi

associated-with-me

sanmi

meal.

mi mo'i ca'uvu citka le mi sanmi

I [movement] [front-long] eat the associated-with-me meal.

While moving a long way forward, I eat my meal.

(Perhaps I am eating in an airplane.)

There is no parallel facility in Lojban at present for expressing movement in time – time travel – but one could be added easily if it ever becomes useful.

10.9. Interval properties: TAhE and roi

The following cmavo are discussed in this section:

| di'i | TAhE | regularly |

| na'o | TAhE | typically |

| ru'i | TAhE | continuously |

| ta'e | TAhE | habitually |

| di'inai | TAhE | irregularly |

| na'onai | TAhE | atypically |

| ru'inai | TAhE | intermittently |

| ta'enai | TAhE | contrary to habit |

| roi | ROI | “n” times |

| roinai | ROI | other than “n” times |

| ze'e | ZEhA | whole time interval |

| ve'e | VEhA | whole space interval |

Consider Lojban bridi which express events taking place in time. Whether a very short interval (a point) or a long interval of time is involved, the event may not be spread consistently throughout that interval. Lojban can use the cmavo of selma'o TAhE to express the idea of continuous or non-continuous actions.

Example 10.40.

mi

I

puzu

[past-long-distance]

ze'u

[long-interval]

velckule

am-a-school-attendee (pupil).

mi puzu ze'u velckule

I [past-long-distance] [long-interval] am-a-school-attendee (pupil).

Long ago I attended school for a long time.

probably does not mean that I attended school continuously throughout the whole of that long-ago interval. Actually, I attended school every day, except for school holidays. More explicitly,

Example 10.41.

mi

I

puzu

[past-long-distance]

ze'u

[long-interval]

di'i

[regularly]

velckule

am-a-pupil.

mi puzu ze'u di'i velckule

I [past-long-distance] [long-interval] [regularly] am-a-pupil.

Long ago I regularly attended school for a long time.

The four TAhE cmavo are differentiated as follows: ru'i covers the entirety of the interval, di'i covers the parts of the interval which are systematically spaced subintervals; na'o covers part of the interval, but exactly which part is determined by context; ta'e covers part of the interval, selected with reference to the behavior of the actor (who often, but not always, appears in the x1 place of the bridi).

Using TAhE does not require being so specific. Either the time direction or the time interval or both may be omitted (in which case they are vague). For example:

Example 10.42.

mi

I

I

ba

[future]

will

ta'e

[habitually]

habitually

klama

go-to

go to

le

the

the

zarci

market.

market.

mi ba ta'e klama le zarci

I [future] [habitually] go-to the market.

I will habitually go to the market.

I will make a habit of going to the market.

specifies the future, but the duration of the interval is indefinite. Similarly,

Example 10.43.

mi

I

na'o

[typically]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi na'o klama le zarci

I [typically] go-to the market.

I typically go/went/will go to the market.

illustrates an interval property in isolation. There are no distance or direction cmavo, so the point of time is vague; likewise, there is no interval cmavo, so the length of the interval during which these goings-to-the-market take place is also vague. As always, context will determine these vague values.

“Intermittently” is the polar opposite notion to “continuously”, and is expressed not with its own cmavo, but by adding the negation suffix -nai (which belongs to selma'o NAI) to ru'i. For example:

Example 10.44.

le

The

verba

child

ru'inai

[continuously-not]

cadzu

walks-on

le

the

bisli

ice.

le verba ru'inai cadzu le bisli

The child [continuously-not] walks-on the ice.

The child intermittently walks on the ice.

As shown in the cmavo table above, all the cmavo of TAhE may be negated with -nai; ru'inai and di'inai are probably the most useful.

An intermittent event can also be specified by counting the number of times during the interval that it takes place. The cmavo roi (which belongs to selma'o ROI) can be appended to a number to make a quantified tense. Quantified tenses are common in English, but not so commonly named: they are exemplified by the adverbs “never”, “once”, “twice”, “thrice”, ... “always”, and by the related phrases “many times”, “a few times”, “too many times”, and so on. All of these are handled in Lojban by a number plus -roi:

Example 10.45.

mi

I

paroi

[one-time]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi paroi klama le zarci

I [one-time] go-to the market.

I go to the market once.

Example 10.46.

mi

I

du'eroi

[too-many-times]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi du'eroi klama le zarci

I [too-many-times] go-to the market.

I go to the market too often.

With the quantified tense alone, we don't know whether the past, the present, or the future is intended, but of course the quantified tense need not stand alone:

Example 10.47.

mi

I

pu

[past]

reroi

[two-times]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi pu reroi klama le zarci

I [past] [two-times] go-to the market.

I went to the market twice.

The English is slightly over-specific here: it entails that both goings-to-the-market were in the past, which may or may not be true in the Lojban sentence, since the implied interval is vague. Therefore, the interval may start in the past but extend into the present or even the future.

Adding -nai to roi is also permitted, and has the meaning “other than (the number specified)”:

Example 10.48.

le

The

ratcu

rat

reroinai

[twice-not]

citka

eats

le

the

cirla

cheese.

le ratcu reroinai citka le cirla

The rat [twice-not] eats the cheese.

The rat eats the cheese other than twice.

This may mean that the rat eats the cheese fewer times, or more times, or not at all.

It is necessary to be careful with sentences like Example 10.45 and Example 10.47, where a quantified tense appears without an interval. What Example 10.47 really says is that during an interval of unspecified size, at least part of which was set in the past, the event of my going to the market happened twice. The example says nothing about what happened outside that vague time interval. This is often less than we mean. If we want to nail down that I went to the market once and only once, we can use the cmavo ze'e which represents the “whole time interval”: conceptually, an interval which stretches from time's beginning to its end:

Example 10.49.

mi

I

ze'e

[whole-interval]

paroi

[once]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi ze'e paroi klama le zarci

I [whole-interval] [once] go-to the market.

Since specifying no ZEhA leaves the interval vague, Example 10.47 might in appropriate context mean the same as Example 10.49 after all – but Example 10.49 allows us to be specific when specificity is necessary.

A PU cmavo following ze'e has a slightly different meaning from one that follows another ZEhA cmavo. The compound cmavo ze'epu signifies the interval stretching from the infinite past to the reference point (wherever the imaginary journey has taken you); ze'eba is the interval stretching from the reference point to the infinite future. The remaining form, ze'eca, makes specific the “whole of time” interpretation just given. These compound forms make it possible to assert that something has never happened without asserting that it never will.

Example 10.50.

mi

I

ze'epu

[whole-interval-past]

noroi

[never]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi ze'epu noroi klama le zarci

I [whole-interval-past] [never] go-to the market.

I have never gone to the market.

says nothing about whether I might go in future.

The space equivalent of ze'e is ve'e, and it can be used in the same way with a quantified space tense: see Section 10.11 for an explanation of space interval modifiers.

10.10. Event contours: ZAhO and re'u

The following cmavo are discussed in this section:

| pu'o | ZAhO | inchoative |

| ca'o | ZAhO | continuitive |

| ba'o | ZAhO | perfective |

| co'a | ZAhO | initiative |

| co'u | ZAhO | cessitive |

| mo'u | ZAhO | completitive |

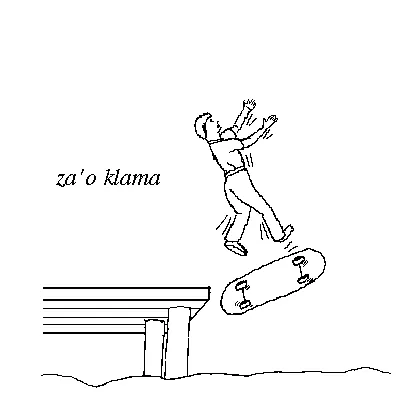

| za'o | ZAhO | superfective |

| co'i | ZAhO | achievative |

| de'a | ZAhO | pausative |

| di'a | ZAhO | resumptive |

| re'u | ROI | ordinal tense |

The cmavo of selma'o ZAhO express the Lojban version of what is traditionally called “aspect”. This is not a notion well expressed by English tenses, but many languages (including Chinese and Russian among Lojban's six source languages) consider it more important than the specification of mere position in time.

The “event contours” of selma'o ZAhO, with their bizarre keywords, represent the natural portions of an event considered as a process, an occurrence with an internal structure including a beginning, a middle, and an end. Since the keywords are scarcely self-explanatory, each ZAhO will be explained in detail here. Note that from the viewpoint of Lojban syntax, ZAhOs are interval modifiers like TAhEs or ROI compounds; if both are found in a single tense, the TAhE/ROI comes first and the ZAhO afterward. The imaginary journey described by other tense cmavo moves us to the portion of the event-as-process which the ZAhO specifies.

It is important to understand that ZAhO cmavo, unlike the other tense cmavo, specify characteristic portions of the event, and are seen from an essentially timeless perspective. The “beginning” of an event is the same whether the event is in the speaker's present, past, or future. It is especially important not to confuse the speaker-relative viewpoint of the PU tenses with the event-relative viewpoint of the ZAhO tenses.

The cmavo pu'o, ca'o, and ba'o (etymologically derived from the PU cmavo) refer to an event that has not yet begun, that is in progress, or that has ended, respectively:

Example 10.51.

mi

I

pu'o

[inchoative]

damba

fight.

mi pu'o damba

I [inchoative] fight.

I'm on the verge of fighting.

Example 10.52.

la

That-named

stiv.

Steve

ca'o

[continuitive]

bacru

utters.

la stiv. ca'o bacru

That-named Steve [continuitive] utters.

Steve continues to talk.

Example 10.53.

le

The

verba

child

ba'o

[perfective]

cadzu

walks-on

le

the

bisli

ice.

le verba ba'o cadzu le bisli

The child [perfective] walks-on the ice.

The child is finished walking on the ice.

As discussed in Section 10.6, the simple PU cmavo make no assumptions about whether the scope of a past, present, or future event extends into one of the other tenses as well. Example 10.51 through Example 10.53 illustrate that these ZAhO cmavo do make such assumptions possible: the event in Example 10.51 has not yet begun, definitively; likewise, the event in Example 10.53 is definitely over.

Note that in Example 10.51 and Example 10.53, pu'o and ba'o may appear to be reversed: pu'o, although etymologically connected with pu, is referring to a future event; whereas ba'o, connected with ba, is referring to a past event. This is the natural result of the event-centered view of ZAhO cmavo. The inchoative, or pu'o, part of an event, is in the “pastward” portion of that event, when seen from the perspective of the event itself. It is only by inference that we suppose that Example 10.51 refers to the speaker's future: in fact, no PU tense is given, so the inchoative part of the event need not be coincident with the speaker's present: pu'o is not necessarily, though in fact often is, the same as ca pu'o.

The cmavo in Example 10.51 through Example 10.53 refer to spans of time. There are also two points of time that can be usefully associated with an event: the beginning, marked by co'a, and the end, marked by co'u. Specifically, co'a marks the boundary between the pu'o and ca'o parts of an event, and co'u marks the boundary between the ca'o and ba'o parts:

Example 10.54.

mi

I

ba

[future]

co'a

[initiative]

citka

eat

le

the

mi

associated-with-me

sanmi

meal.

mi ba co'a citka le mi sanmi

I [future] [initiative] eat the associated-with-me meal.

I will begin to eat my meal.

Example 10.55.

mi

I

pu

[past]

co'u

[cessitive]

citka

eat

le

the

mi

associated-with-me

sanmi

meal.

mi pu co'u citka le mi sanmi

I [past] [cessitive] eat the associated-with-me meal.

I ceased eating my meal.

Compare Example 10.54 with:

Example 10.56.

mi

I

ba

[future]

di'i

[regularly]

co'a

[initiative]

bajra

run.

mi ba di'i co'a bajra

I [future] [regularly] [initiative] run.

I will regularly begin to run.

which illustrates the combination of a TAhE with a ZAhO.

A process can have two end points, one reflecting the “natural end” (when the process is complete) and the other reflecting the “actual stopping point” (whether complete or not). Example 10.55 may be contrasted with:

Example 10.57.

mi

I

pu

[past]

mo'u

[completitive]

citka

eat

le

the

mi

associated-with-me

sanmi

meal.

mi pu mo'u citka le mi sanmi

I [past] [completitive] eat the associated-with-me meal.

I finished eating my meal.

In Example 10.57, the meal has reached its natural end; in Example 10.55, the meal has merely ceased, without necessarily reaching its natural end.

A process such as eating a meal does not necessarily proceed uninterrupted. If it is interrupted, there are two more relevant point events: the point just before the interruption, marked by de'a, and the point just after the interruption, marked by di'a. Some examples:

Example 10.58.

mi

I

pu

[past]

de'a

[pausative]

citka

eat

le

the

mi

associated-with-me

sanmi

meal.

mi pu de'a citka le mi sanmi

I [past] [pausative] eat the associated-with-me meal.

I stopped eating my meal (with the intention of resuming).

Example 10.59.

mi

I

ba

[future]

di'a

[resumptive]

citka

eat

le

the

mi

associated-with-me

sanmi

meal.

mi ba di'a citka le mi sanmi

I [future] [resumptive] eat the associated-with-me meal.

I will resume eating my meal.

In addition, it is possible for a process to continue beyond its natural end. The span of time between the natural and the actual end points is represented by za'o:

Example 10.60.

le

The

ctuca

teacher

pu

[past]

za'o

[superfective]

ciksi

explained

le

the

cmaci

mathematics

seldanfu

problem

le

to-the

tadgri

student-group.

le ctuca pu za'o ciksi le cmaci seldanfu le tadgri

The teacher [past] [superfective] explained the mathematics problem to-the student-group.

The teacher kept on explaining the mathematics problem to the class too long.

That is, the teacher went on explaining after the class already understood the problem.

An entire event can be treated as a single moment using the cmavo co'i:

Example 10.61.

la

That-named

djan.

John

pu

[past]

co'i

[achievative]

catra

kills

la

that-named

djim

Jim.

la djan. pu co'i catra la djim

That-named John [past] [achievative] kills that-named Jim.

John was at the point in time where he killed Jim.

Finally, since an activity is cyclical, an individual cycle can be referred to using a number followed by re'u, which is the other cmavo of selma'o ROI:

Example 10.62.

mi

I

pare'u

[first-time]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

store.

mi pare'u klama le zarci

I [first-time] go-to the store.

I go to the store for the first time (within a vague interval).

Note the difference between:

Example 10.63.

mi

I

pare'u

[first-time]

paroi

[one-time]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

store.

mi pare'u paroi klama le zarci

I [first-time] [one-time] go-to the store.

For the first time, I go to the store once.

and

Example 10.64.

mi

I

paroi

[one-time]

pare'u

[first-time]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

store.

mi paroi pare'u klama le zarci

I [one-time] [first-time] go-to the store.

There is one occasion on which I go to the store for the first time.

10.11. Space interval modifiers: FEhE

The following cmavo is discussed in this section:

| fe'e | FEhE | space interval modifier flag |

Like time intervals, space intervals can also be continuous, discontinuous, or repetitive. Rather than having a whole separate set of selma'o for space interval properties, we instead prefix the flag fe'e to the cmavo used for time interval properties. A space interval property would be placed just after the space interval size and/or dimensionality cmavo:

Example 10.65.

ko

You-imperative

vi'i

[1-dimensional]

fe'e

[space:]

di'i

[regularly]

sombo

sow

le

the

gurni

grain.

ko vi'i fe'e di'i sombo le gurni

You-imperative [1-dimensional] [space:] [regularly] sow the grain.

Sow the grain in a line and evenly!

Example 10.66.

mi

I

fe'e

[space:]

ciroi

[three-places]

tervecnu

buy

lo

those-which-are

selsalta

salad-ingredients.

mi fe'e ciroi tervecnu lo selsalta

I [space:] [three-places] buy those-which-are salad-ingredients.

I buy salad ingredients in three locations.

Example 10.67.

ze'e

[whole-time]

roroi

[all-times]

ve'e

[whole-space]

fe'e

[space:]

roroi

[all-places]

ku

li

The-number

re

su'i

re

du

li

the-number

vo

.

ze'e roroi ve'e fe'e roroi ku li re su'i re du li vo

[whole-time] [all-times] [whole-space] [space:] [all-places] The-number the-number .

Always and everywhere, two plus two is four.

As shown in Example 10.67, when a tense comes first in a bridi, rather than in its normal position before the selbri (in this case du), it is emphasized.

The fe'e marker can also be used for the same purpose before members of ZAhO. (The cmavo be'a belongs to selma'o FAhA; it is the space direction meaning “north of”.)

Example 10.68.

tu

That-yonder

ve'abe'a

[medium-space-interval-north]

fe'e

[space]

co'a

[initiative]

rokci

is-a-rock.

tu ve'abe'a fe'e co'a rokci

That-yonder [medium-space-interval-north] [space] [initiative] is-a-rock.

That is the beginning of a rock extending to my north.

That is the south face of a rock.

Here the notion of a “beginning point” represented by the cmavo co'a is transferred from “beginning in time” to “beginning in space” under the influence of the fe'e flag. Space is not inherently oriented, unlike time, which flows from past to future: therefore, some indication of orientation is necessary, and the ve'abe'a provides an orientation in which the south face is the “beginning” and the north face is the “end”, since the rock extends from south (near me) to north (away from me).

Many natural languages represent time by a space-based metaphor: in English, what is past is said to be “behind us”. In other languages, the metaphor is reversed. Here, Lojban is representing space (or space interval modifiers) by a time-based metaphor: the choice of a FAhA cmavo following a VEhA cmavo indicates which direction is mapped onto the future. (The choice of future rather than past is arbitrary, but convenient for English-speakers.)

If both a TAhE (or ROI) and a ZAhO are present as space interval modifiers, the fe'e flag must be prefixed to each.

10.12. Tenses as sumti tcita

So far, we have seen tenses only just before the selbri, or (equivalently in meaning) floating about the bridi with ku. There is another major use for tenses in Lojban: as sumti tcita, or argument tags. A tense may be used to add spatial or temporal information to a bridi as, in effect, an additional place:

Example 10.69.

mi

I

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market

ca

[present]

le

the

nu

event-of

do

you

klama

go-to

le

the

zdani

house.

mi klama le zarci ca le nu do klama le zdani

I go-to the market [present] the event-of you go-to the house.

I go to the market when you go to the house.

Here ca does not appear before the selbri, nor with ku; instead, it governs the following sumti, the le nu construct. What Example 10.69 asserts is that the action of the main bridi is happening at the same time as the event mentioned by that sumti. So ca, which means “now” when used with a selbri, means “simultaneously-with” when used with a sumti. Consider another example:

Example 10.70.

mi

I

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market

pu

[past]

le

the

nu

event-of

do

you

pu

[past]

klama

go-to

le

the

zdani

house.

mi klama le zarci pu le nu do pu klama le zdani

I go-to the market [past] the event-of you [past] go-to the house.

The second pu is simply the past tense marker for the event of your going to the house, and says that this event is in the speaker's past. How are we to understand the first pu, the sumti tcita?

All of our imaginary journeys so far have started at the speaker's location in space and time. Now we are specifying an imaginary journey that starts at a different location, namely at the event of your going to the house. Example 10.70 then says that my going to the market is in the past, relative not to the speaker's present moment, but instead relative to the moment when you went to the house. Example 10.70 can therefore be translated:

I had gone to the market before you went to the house.

(Other translations are possible, depending on the ever-present context.) Spatial direction and distance sumti tcita are exactly analogous:

Example 10.71.

le

The

ratcu

rat

cu

citka

eats

le

the

cirla

cheese

vi

[short-time-distance]

le

the

panka

park.

le ratcu cu citka le cirla vi le panka

The rat eats the cheese [short-time-distance] the park.

The rat eats the cheese near the park.

Example 10.72.

le

The

ratcu

rat

cu

citka

eats

le

the

cirla

cheese

vi

[short-distance]

le

the

vu

[long-distance]

panka

park

le ratcu cu citka le cirla vi le vu panka

The rat eats the cheese [short-distance] the [long-distance] park

The rat eats the cheese near the faraway park.

Example 10.73.

le

The

ratcu

rat

cu

citka

eats

le

the

cirla

cheese

vu

[long-distance]

le

the

vi

[short-distance]

panka

park

le ratcu cu citka le cirla vu le vi panka

The rat eats the cheese [long-distance] the [short-distance] park

The rat eats the cheese far away from the nearby park.

The event contours of selma'o ZAhO (and their space equivalents, prefixed with fe'e) are also useful as sumti tcita. The interpretation of ZAhO tcita differs from that of FAhA, VA, PU, and ZI tcita, however. The event described in the sumti is viewed as a process, and the action of the main bridi occurs at the phase of the process which the ZAhO specifies, or at least some part of that phase. The action of the main bridi itself is seen as a point event, so that there is no issue about which phase of the main bridi is intended. For example:

Example 10.74.

mi

I

morsi

am-dead

ba'o

[perfective]

le

the

nu

event-of

mi

I

jmive

live.

mi morsi ba'o le nu mi jmive

I am-dead [perfective] the event-of I live.

I die in the aftermath of my living.

Here the (point-)event of my being dead is the portion of my living-process which occurs after the process is complete. Contrast Example 10.74 with:

Example 10.75.

mi

I

morsi

am-dead

ba

[future]

le

the

nu

event-of

mi

I

jmive

live.

mi morsi ba le nu mi jmive

I am-dead [future] the event-of I live.

As explained in Section 10.6, Example 10.75 does not exclude the possibility that I died before I ceased to live!

Likewise, we might say:

Example 10.76.

mi

I

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

store

pu'o

[inchoative]

le

the

nu

event-of

mi

I

citka

eat

mi klama le zarci pu'o le nu mi citka

I go-to the store [inchoative] the event-of I eat

which indicates that before my eating begins, I go to the store, whereas

Example 10.77.

mi

I

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

store

ba'o

[perfective]

le

the

nu

event-of

mi

I

citka

eat

mi klama le zarci ba'o le nu mi citka

I go-to the store [perfective] the event-of I eat

would indicate that I go to the store after I am finished eating.

Here is an example which mixes temporal ZAhO (as a tense) and spatial ZAhO (as a sumti tcita):

Example 10.78.

le

The

bloti

boat

pu

[past]

za'o

[superfective]

xelklama

is-a-transport-mechanism

fe'e

[space]

ba'o

[perfective]

le

the

lalxu

lake.

le bloti pu za'o xelklama fe'e ba'o le lalxu

The boat [past] [superfective] is-a-transport-mechanism [space] [perfective] the lake.

The boat sailed for too long and beyond the lake.

Probably it sailed up onto the dock. One point of clarification: although xelklama appears to mean simply “is-a-mode-of-transport”, it does not – the bridi of Example 10.78 has four omitted arguments, and thus has the (physical) journey which goes on too long as part of its meaning.

The remaining tense cmavo, which have to do with interval size, dimension, and continuousness (or lack thereof) are interpreted to let the sumti specify the particular interval over which the main bridi operates:

Example 10.79.

mi

I

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market

reroi

[twice]

le

the

ca

[present]

djedi

day.

mi klama le zarci reroi le ca djedi

I go-to the market [twice] the [present] day.

I go/went/will go to the market twice today.

Be careful not to confuse a tense used as a sumti tcita with a tense used within a seltcita sumti:

Example 10.80.

loi

Some-of-the-mass-of

snime

snow

cu

carvi

rains

ze'u

[long-time-interval]

le

the

ca

[present]

dunra

winter.

loi snime cu carvi ze'u le ca dunra

Some-of-the-mass-of snow rains [long-time-interval] the [present] winter.

Snow falls during this winter.

claims that the interval specified by “this winter” is long, as events of snowfall go, whereas

Example 10.81.

loi

Some-of-the-mass-of

snime

snow

cu

carvi

rains

ca

[present]

le

the

ze'u

[long-time]

dunra

winter.

loi snime cu carvi ca le ze'u dunra

Some-of-the-mass-of snow rains [present] the [long-time] winter.

Snow falls in the long winter.

claims that during some part of the winter, which is long as winters go, snow falls.

10.13. Sticky and multiple tenses: KI

The following cmavo is discussed in this section:

| ki | KI | sticky tense set/reset |

So far we have only considered tenses in isolated bridi. Lojban provides several ways for a tense to continue in effect over more than a single bridi. This property is known as “stickiness”: the tense gets “stuck” and remains in effect until explicitly “unstuck”. In the metaphor of the imaginary journey, the place and time set by a sticky tense may be thought of as a campsite or way-station: it provides a permanent origin with respect to which other tenses are understood. Later imaginary journeys start from that point rather than from the speaker.

To make a tense sticky, suffix ki to it:

Example 10.82.

mi

I

puki

[past-sticky]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

.i

le

The

nanmu

man

cu

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

mi puki klama le zarci .i le nanmu cu batci le gerku

I [past-sticky] go-to the market. The man bites the dog.

I went to the market. The man bit the dog.

Here the use of puki rather than just pu ensures that the tense will affect the next sentence as well. Otherwise, since the second sentence is tenseless, there would be no way of determining its tense; the event of the second sentence might happen before, after, or simultaneously with that of the first sentence.

(The last statement does not apply when the two sentences form part of a narrative. See Section 10.14 for an explanation of “story time”, which employs a different set of conventions.)

What if the second sentence has a tense anyway?

Example 10.83.

mi

I

puki

[past-sticky]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

.i

le

The

nanmu

man

pu

[past]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

mi puki klama le zarci .i le nanmu pu batci le gerku

I [past-sticky] go-to the market. The man [past] bites the dog.

Here the second pu does not replace the sticky tense, but adds to it, in the sense that the starting point of its imaginary journey is taken to be the previously set sticky time. So the translation of Example 10.83 is:

Example 10.84.

I went to the market. The man had earlier bitten the dog.

and it is equivalent in meaning (when considered in isolation from any other sentences) to:

Example 10.85.

mi

I

pu

[past]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi pu klama le zarci

I [past] go-to the market.

.i

le

The

nanmu

man

pupu

[past-past]

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

.i le nanmu pupu batci le gerku

The man [past-past] bites the dog.

The point has not been discussed so far, but it is perfectly grammatical to have more than one tense construct in a sentence:

Example 10.86.

puku

[past]

mi

I

ba

[future]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

puku mi ba klama le zarci

[past] I [future] go-to the market.

Earlier, I was going to go to the market.

Here there are two tenses in the same bridi, the first floating free and specified by puku, the second in the usual place and specified by ba. They are considered cumulative in the same way as the two tenses in separate sentences of Example 10.85. Example 10.86 is therefore equivalent in meaning, except for emphasis, to:

Example 10.87.

mi

I

puba

[past-future]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi puba klama le zarci

I [past-future] go-to the market.

I was going to go to the market.

Compare Example 10.88 and Example 10.89, which have a different meaning from Example 10.86 and Example 10.87:

Example 10.88.

mi

I

ba

[future]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market

puku

[past].

mi ba klama le zarci puku

I [future] go-to the market [past].

I will have gone to the market earlier.

Example 10.89.

mi

I

bapu

[future-past]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

mi bapu klama le zarci

I [future-past] go-to the market.

I will have gone to the market.

So when multiple tense constructs in a single bridi are involved, order counts – the tenses cannot be shifted around as freely as if there were only one tense to worry about.

But why bother to allow multiple tense constructs at all? They specify separate portions of the imaginary journey, and can be useful in order to make part of a tense sticky. Consider Example 10.90, which adds a second bridi and a ki to Example 10.86:

Example 10.90.

pu

[past]

ki

[sticky]

ku

mi

I

ba

[future]

klama

go-to

le

the

zarci

market.

.i

le

The

nanmu

man

cu

batci

bites

le

the

gerku

dog.

pu ki ku mi ba klama le zarci .i le nanmu cu batci le gerku

[past] [sticky] I [future] go-to the market. The man bites the dog.

What is the implied tense of the second sentence? Not puba, but only pu, since only pu was made sticky with ki. So the translation is:

I was going to go to the market. The man bit the dog.

Lojban has several ways of embedding a bridi within another bridi: descriptions, abstractors, relative clauses. (Technically, descriptions contain selbri rather than bridi.) Any of the selbri of these subordinate bridi may have tenses attached. These tenses are interpreted relative to the tense of the main bridi:

Example 10.91.

mi

I

pu

[past]

klama

go-to

le

the

ba'o

[perfective]

zarci

market

mi pu klama le ba'o zarci

I [past] go-to the [perfective] market

I went to the former market.

The significance of the ba'o in Example 10.91 is that the speaker's destination is described as being “in the aftermath of being a market”; that is, it is a market no longer. In particular, the time at which it was no longer a market is in the speaker's past, because the ba'o is interpreted relative to the pu tense of the main bridi.

Here is an example involving an abstraction bridi:

Example 10.92.

mi

I

ca

now

jinvi

opine

le

the

du'u

fact-that

mi

I

ba

will-be

morsi

dead.

mi ca jinvi le du'u mi ba morsi

I now opine the fact-that I will-be dead.

I now believe that I will be dead.

Here the event of being dead is said to be in the future with respect to the opinion, which is in the present.

ki may also be used as a tense by itself. This cancels all stickiness and returns the bridi and all following bridi to the speaker's location in both space and time.

In complex descriptions, multiple tenses may be saved and then used by adding a subscript to ki. A time made sticky with kixipa (ki-sub-1) can be returned to by specifying kixipa as a tense by itself. In the case of written expression, the writer's here-and-now is often different from the reader's, and a pair of subscripted ki tenses could be used to distinguish the two.

10.14. Story time

Making strict use of the conventions explained in Section 10.13 would be intolerably awkward when a story is being told. The time at which a story is told by the narrator is usually unimportant to the story. What matters is the flow of time within the story itself. The term “story” in this section refers to any series of statements related in more-or-less time-sequential order, not just a fictional one.

Lojban speakers use a different set of conventions, commonly called “story time”, for inferring tense within a story. It is presumed that the event described by each sentence takes place some time more or less after the previous ones. Therefore, tenseless sentences are implicitly tensed as “what happens next”. In particular, any sticky time setting is advanced by each sentence.

The following mini-story illustrates the important features of story time. A sentence-by-sentence explication follows:

Example 10.93.

pu

[past]

zu

[long]

ki

[sticky]

ku

[,]

ne'i

[inside]

ki

[sticky]

le

the

kevna

cave,

le

the

ninmu

woman

goi

defined-as

ko'a

she-1

zutse

sat-on

le

the

rokci

rock

pu zu ki ku ne'i ki le kevna le ninmu goi ko'a zutse le rokci

[past] [long] [sticky] [,] [inside] [sticky] the cave, the woman defined-as she-1 sat-on the rock

Long ago, in a cave, a woman sat on a rock.

Example 10.94.

.i

ko'a

She-1

citka

eat-(tenseless)

loi

some-of-the-mass-of

kanba

goat

rectu

flesh.

.i ko'a citka loi kanba rectu

She-1 eat-(tenseless) some-of-the-mass-of goat flesh.

She was eating goat's meat.

Example 10.95.

.i

ko'a

She

pu

[past]

jukpa

cook

ri

the-last-mentioned

le

by-method-the

mudyfagri

wood-fire.

.i ko'a pu jukpa ri le mudyfagri

She [past] cook the-last-mentioned by-method-the wood-fire.

She had cooked the meat over a wood fire.

Example 10.96.

.i

lei

The-mass-of

rectu

flesh

cu

zanglare

is-(favorable)-warm.

.i lei rectu cu zanglare

The-mass-of flesh is-(favorable)-warm.

The meat was pleasantly warm.

Example 10.97.

.i

le

The

labno

wolf

goi

defined-as

ko'e

it-2

ba

[future]

za

[medium]

ki

[sticky]

nenri

within

klama

came

le

to-the

kevna

cave.

.i le labno goi ko'e ba za ki nenri klama le kevna

The wolf defined-as it-2 [future] [medium] [sticky] within came to-the cave.

A while later, a wolf came into the cave.

Example 10.98.

.i

ko'e

It-2

lebna

takes-(tenseless)

lei

the-mass-of

rectu

flesh

ko'a

from-her-1.

.i ko'e lebna lei rectu ko'a

It-2 takes-(tenseless) the-mass-of flesh from-her-1.

It took the meat from her.

Example 10.99.

.i

ko'e

It-2

bartu

out

klama

ran

.i ko'e bartu klama

It-2 out ran

It ran out.

Example 10.93 sets both the time (long ago) and the place (in a cave) using ki, just like the sentence sequences in Section 10.13. No further space cmavo are used in the rest of the story, so the place is assumed to remain unchanged. The English translation of Example 10.93 is marked for past tense also, as the conventions of English storytelling require: consequently, all other English translation sentences are also in the past tense. (We don't notice how strange this is; even stories about the future are written in past tense!) This conventional use of past tense is not used in Lojban narratives.

Example 10.94 is tenseless. Outside story time, it would be assumed that its event happens simultaneously with that of Example 10.93, since a sticky tense is in effect; the rules of story time, however, imply that the event occurs afterwards, and that the story time has advanced (changing the sticky time set in Example 10.93).

Example 10.95 has an explicit tense. This is taken relative to the latest setting of the sticky time; therefore, the event of Example 10.95 happens before that of Example 10.94. It cannot be determined if Example 10.95 happens before or after Example 10.93.

Example 10.96 is again tenseless. Story time was not changed by the flashback in Example 10.95, so Example 10.96 happens after Example 10.94.

Example 10.97 specifies the future (relative to Example 10.96) and makes it sticky. So all further events happen after Example 10.97.

Example 10.98 and Example 10.99 are again tenseless, and so happen after Example 10.97. (Story time is changed.)

So the overall order is Example 10.93 - Example 10.95 - Example 10.94 - Example 10.96 - (medium interval) - Example 10.97 - Example 10.98 - Example 10.99. It is also possible that Example 10.95 happens before Example 10.93.

If no sticky time (or space) is set initially, the story is set at an unspecified time (or space): the effect is like that of choosing an arbitrary reference point and making it sticky. This style is common in stories that are jokes. The same convention may be used if the context specifies the sticky time sufficiently.

10.15. Tenses in subordinate bridi

English has a set of rules, formally known as “sequence of tense rules”, for determining what tense should be used in a subordinate clause, depending on the tense used in the main sentence. Here are some examples:

Example 10.100.

John says that George is going to the market.

Example 10.101.

John says that George went to the market.

Example 10.102.

John said that George went to the market.

Example 10.103.

John said that George had gone to the market.

In Example 10.100 and Example 10.101, the tense of the main sentence is the present: “says”. If George goes when John speaks, we get the present tense “is going” (“goes” would be unidiomatic); if George goes before John speaks, we get the past tense “went”. But if the tense of the main sentence is the past, with “said”, then the tense required in the subordinate clause is different. If George goes when John speaks, we get the past tense “went”; if George goes before John speaks, we get the past-perfect tense “had gone”.

The rule of English, therefore, is that both the tense of the main sentence and the tense of the subordinate clause are understood relative to the speaker of the main sentence (not John, but the person who speaks Example 10.100 through Example 10.103).

Lojban, like Russian and Esperanto, uses a different convention. A tense in a subordinate bridi is understood to be relative to the tense already set in the main bridi. Thus Example 10.100 through Example 10.103 can be expressed in Lojban respectively thus:

Example 10.104.

la

djan.

John

ca

[present]

cusku

says

le

the

se

du'u

statement-that

la

That-named

djordj.

George

ca

[present]

klama

goes-to

le

the

zarci

market.

la djan. ca cusku le se du'u la djordj. ca klama le zarci